Different Ways to Attack a QUANT Question — Part 3

In this final segment of this three-part series on Different Ways to Attack a Quant Question, we’ll investigate the Conceptual approach to the problem below:

In order to complete a reading assignment on time, Terry planned to read 90 pages per day. However, she read only 75 pages per day at first, leaving 690 pages to be read during the last 6 days before the assignment was to be completed. How many days in all did Terry have to complete the assignment on time?

(A) 15

(B) 16

(C) 25

(D) 40

(E) 46

Source: Official Guide 2015, PS 119

Please make sure that you have read part 1 and part 2 of this series before you proceed since this article builds on those.

As its name implies, the Conceptual approach centers around a key concept or property that is present in the problem. That concept/property may be what the author was intentionally testing, or it just may just represent a faster or more “clever” approach for solving the problem. In the question above, I would consider it more the latter.

Two Conceptual Approaches Here

There are in fact two slightly different Conceptual approaches to this question, and we’ll cover both here. They both relate to the topic of statistics, specifically averages, but the perspectives are slightly different. The first relates to the idea of an average as a balance. The second uses the concept of weighted averages.

For both approaches, we can think about Terry’s intended constant rate of 90 pp/day (i.e. the PLAN) as an average rate that needs to be achieved. In the ACTUAL scenario, she doesn’t manage to maintain a constant rate throughout, but the average must still be the same, otherwise she wouldn’t have finished the full assignment in the allotted number of days.

The Average As A Balance

One perspective on an average is that it is the balancing point of all of the statistics it represents. To put it differently, the average is the point that if you calculate the delta (i.e. the difference but with sign indicated) between that point and each statistic in the set, those deltas would net to zero.

Let’s take for example set A {4,7,10,15}, which has an average of 9. If we calculate the deltas between the average and each of the 4 statistics we get {-5,-2,+1,+6}, respectively (i.e. 4-9=-5, 7-9=-2, 10-9=1, 15-9=6). The sum of these deltas we can see is zero: -5 + -2 + 1 + 6 = 0.

We can apply this definition of an average to this problem. The ACTUAL scenario is a set of statistics made up of some unknown number of 75’s (75 pp/day for all but the last 6 days) and six 115’s The 115’s come from taking the sum of the last six days, 690, and dividing by 6. We don’t actually know that there is a constant rate on these last 6 days but for statistical purposes it will work to treat it as such.

Deltas Must Net to Zero

Now we compare the deltas. The six 115’s each have a delta of +25 (i.e. 115 – 90 = 25). And while we don’t know how many 75’s there are, each one would have a delta of -15 (75 – 90). Remember that the deltas must net to zero for 90 to be the average. In other words, some unknown number of -15’s must cancel with six +25’s when you add them up. A quick equation here can help us find the unknown number:

n(-15) + 6(25) = 0

So n = 10

(you might also have just recognized that 6 x 25 = 150, so you need 10 of the -15’s to cancel)

Just be careful here when thinking about the answer. 10 is the number of 75’s, but we still need to add 6 (for the last six days of reading @ 115 pp/day) to get the final answer of 16.

The Weighted Average Solution

The other way to deal with the concept of averages in this question is to view the target rate for the PLAN as a weighted average, specifically of the two different rates that Terry read at in the ACTUAL scenario, the 75 pp/day and the 115 pp/day.

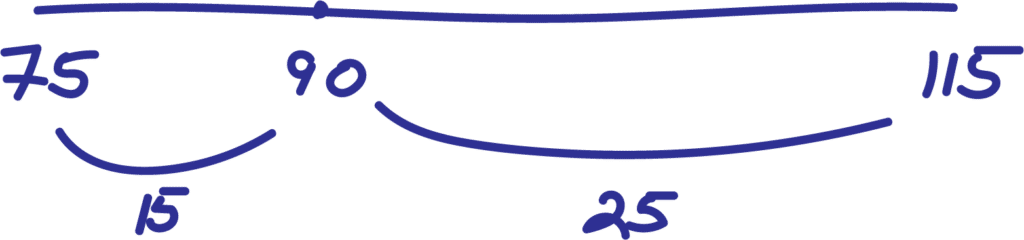

Let’s use a graphical representation of weighted averages, one I call the Tug-of-War method, to analyze the relative weight ratio of the two statistics based on the given weighted average. We first draw a line segment with the values for the two statistics, 75 and 115, placed on the ends of the line segment. Then we place the weighted average, 90, in a position that is logical relative to its value (i.e. closer to the 75 then to the 115). Finally, we’ll calculate the distance that each endpoint (i.e. each statistic) is from the weighted average and mark that on the sketch.

Qualitative Inference

Qualitatively speaking, a weighted average will be closer to the statistic that has a greater weight or that is more represented. Here, that means that there were more days of 75 pp/day reading than there were of 115 pp/day reading, since 90 is closer to 75 than it is to 115.

Quantitative Inference

But it gets even better than that! With this method we are able to infer specific quantitative values as well. The relative weight ratio of the two statistics is the same as the ratio of their two distances from the weighted average. The distances of 15 (90-75) and 25 (115-90) have a ratio of 15:25 or 3:5, so this ratio is also the weight ratio of the two statistics. Here the weighting is based on how many days there are of each rate, i.e. how many days of the 75 pp/day there are vs. how many days of 115 pp/day there are.

Yet while the ratio of the distances is the same as the weight ratio, it’s always backwards or inverted. The closer the distance, actually the greater the weight. So because the 90 is the closer of the two statistics, the days of 90: days of 115 = 5:3. Rather than remember the backwards thing though, just think about it logically like a Tug-of-War match. A statistic that managed to pull the weighted average closer to its side is the “stronger” or more heavily weighted statistic.

There’s one more step to finish up here. If the ratio of number of days of 75 pp/day to number of days of 115 pp/day is 5:3, and we know that there were actually 6 days of 115 pp/day reading, there must have been 10 days of 75 pp/day reading (the ratio is being multiplied by 2). That means that the total number of days is 6 + 10 = 16.

Fast But Difficult to See

Both of these Conceptual approaches rely on the ability to translate this question into a perspective based on averages. And given the fact that this question is not explicitly written this way, that could represent a challenge for many. For this reason you might not consider this your first choice for how to solve this question. You might be thinking, “oh that’s cool, but I would never think to do that”. If that’s the case, I would urge you to challenge yourselves a little. Perhaps reframe it: “I wouldn’t have thought to do this up until today, but now I will notice x, y and z and think about a, b or c”.

More Choices, More Flexibility

In the end you may still prefer the Mathematical (Algebraic) or Practical (Plug-em-back) approach on this question. However, thinking about solving GMAT Quant questions in as many different ways as possible will help develop your flexibility, a key attribute for most highly successful quant scorers.