The C-Trap: a Data Sufficiency Guessing Strategy and Mindset

The hard reality for most on the QUANT section of the GMAT is that strategic (or maybe not-so- strategic!) guessing will play a part in your exam. Faced with the perils of the ticking clock and the need to be extremely accurate on easy / medium questions, there will inevitably come a time to guess and move on. Ideally, some thought and insight go into the guess.

Data Sufficiency (DS) questions are particularly ripe for guessing. After all you don’t actually have to solve the math in a DS question. Caution to the wise, however: the GMAT authors also know that you might be trying to move quickly on DS questions! As such, they intentionally scatter the playing field with pernicious land mines and traps. But we are going to learn to be smarter than them and beat them at their own game.

The C-Trap

One of the most commonly cited guessing strategies in DS is the C-Trap. So what is the C-Trap exactly? I find that many students have heard of it, but few understand it in all its glory. From its name, it obviously means that answer choice C is some kind of trap in the question. But let’s look at an example to get a clearer understanding.

A clothing store acquired an item at a cost of x dollars and sold the item for y dollars. The store’s gross profit from the item was what percent of its cost for the item?

(1) y – x = 20

(2) y/x = 5/4

Source: Official Guide 2015, DS 51

If you are not careful in the question above, you might interpret the fact that the question is asking you to find the gross profit as a percent of cost as simply a call to solve for the unknowns x and y. And it’s true of course that if you know the value of x and y here, you can answer the question at hand. But you don’t actually need them in order to do so.

Two Linear Equations with Two Unknowns

So where does the C-trap come in here? Statements (1) and (2) are both linear equations. As a quick refresher, a linear equation is one that can be graphed as a line in the coordinate system or that can be rewritten in the form of y = mx + b, where m and b are constants. And when you have a system of two unique* linear equations with two unknowns, there will ALWAYS be exactly one solution. That’s because graphically, two lines (that are neither identical nor parallel, the latter of which could never happen in a system of equations in DS) will always intersect at only one point. That means that there would be exactly one x and y solution to the system. So for the problem above that would mean that you would certainly be able to solve if you combined the statements.

*unique (above) refers to the fact that the equations must not be carbon copies of one another just written slightly differently. On occasion the GMAT does play this trick so beware!

Obvious = BAD (probably wrong)

The problem is that most people who sit the GMAT know that a system of two unique and linear equations with two unknowns has a single solution. That makes it pretty patently obvious that with the two statements combined, you can solve! In fact, I would even argue here that you could see that without writing anything down. That in fact is the criterion that I usually give my students for a C-trap:

If you can see that you can easily answer the question with the two statements combined without writing anything down, it is most likely a C-trap!

Remember what answer choice C is really about: the statements are sufficient TOGETHER, but NEITHER statement ALONE is sufficient. When you arrive at a situation in which the two statements OBVIOUSLY WORK together, question whether one (or perhaps even either) also works alone. Why, you might ask? Because the GMAT is almost never that easy. Remember that the test writers have to stratify the test takers’ scores so writing questions that are obvious is the worst thing they can do.

In the question above, it’s obvious when you combine the statements that you can solve for x and y. And that is a loud cry to more carefully consider the INDEPENDENT sufficiency of each of the two statements. There are a few different ways to do so in this question, since this question can be solved with the Mathematical, the Practical or arguably even the Conceptual approach. I’ll just show the Mathematical (i.e. algebraic) approach here since I think it’s the fastest and different ways of solving the question is not our purpose here.

The Mathematical Solution

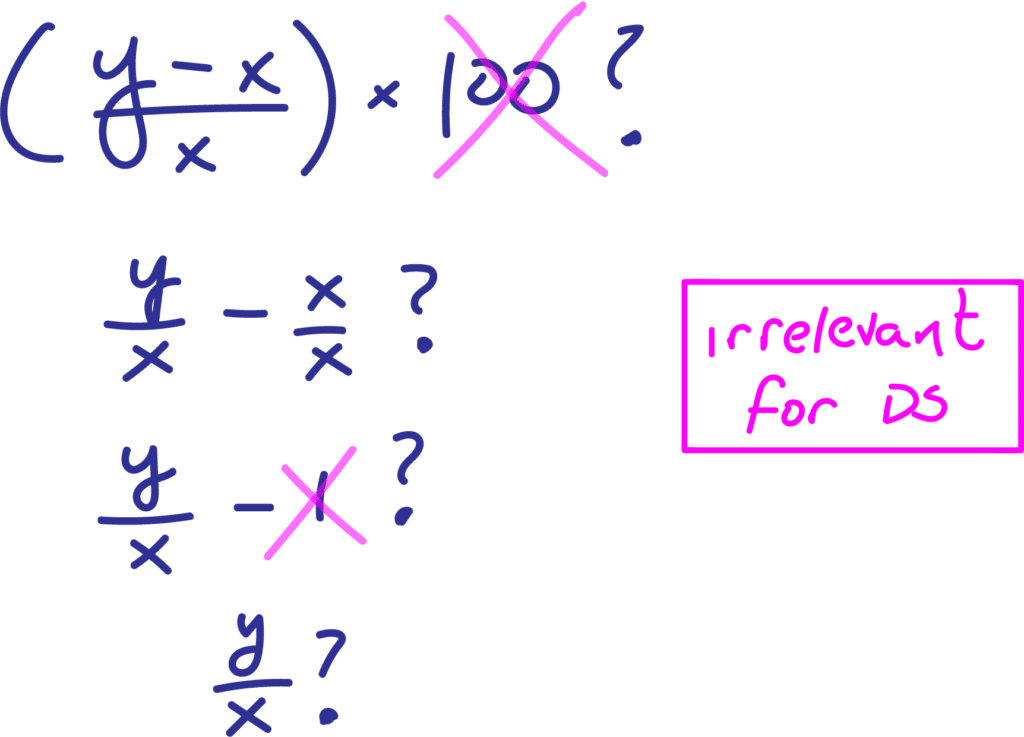

As is always the case in DS, it’s a good idea to first simplify the question stem as much as possible before starting in on the statements. Since the question asks for profit (y – x) as a percent of cost (x), we could formulate and then simplify the question using the following expressions:

After simplifying the question, we can easily spot that statement (2) is sufficient on its own so the answer is B.

So where does the guesswork come in? Well obviously, if you managed to do what I showed above there is no guesswork involved! But let’s say you didn’t, and you made it to the point of combining the two statements. “Oh wait – that’s too obvious”. Thought? “It’s most likely not C, but rather a C-trap.” And when you suspect a C-trap, logically there are three theoretical courses of action.

- Go back and work harder to prove A, B, or less commonly D

- Guess A, B or less commonly D (guess because you don’t have time to do step 1)

- Guess C despite the C-trap concept. ***

Don’t Guess C When You Suspect a C-Trap!

So here’s the funny part. I have been teaching about the C-trap for well over a decade. The concept of “oh that’s so obvious when you combine so it’s probably not C” is not so difficult for most to grasp. What I have found difficult for most to execute, however, is that you should NEVER do #3*** above! NEVER guess C when you suspect a C-trap! NEVER! The whole point of learning about the C-trap as a guessing strategy is that you should never guess C when you suspect a C-trap.

If It’s a C-Trap It Can’t Be “E”

Also I frequently hear people say “I suspected a C-trap, so I put E.” Two possibilities here:

- That person doesn’t really have a grasp of what a C-trap is (C-trap = it’s obvious that they work together but it’s too easy for that to be the end of the story, so it’s likely A, B or D). How then can it be E?

- Maybe it is E, but it’s not a C-trap as we’ve defined it. There may be some kind of trap to get you to put C (i.e. an appearance of sufficiency in the combined), but the C-trap is the term we reserve only for the above.

Don’t Abuse / Overuse the C-Trap

A final warning with regards to the C-trap. Do NOT overuse and abuse it. What does that look like? “I am afraid to put C on a DS question because I thought it was a C-trap”. Do NOT be suspicious of every C. Many, many DS questions resolve to C in the end. Remember that the C is only suspect when it becomes so obvious when you combine (i.e. you don’t even need to write it out).